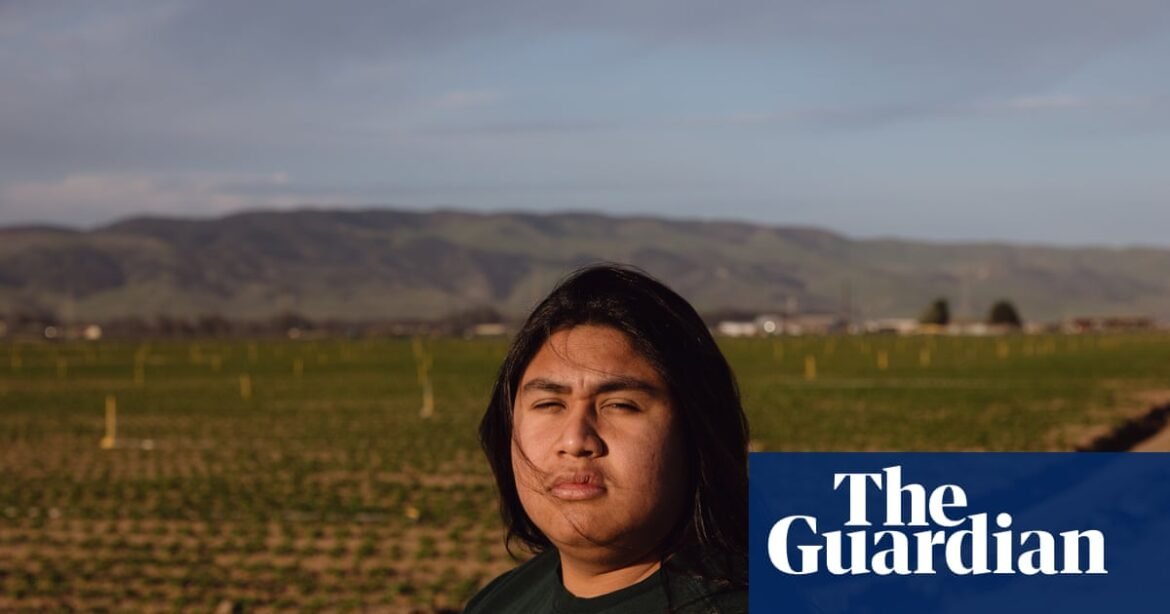

While most 18-year-olds worry about college papers and spring break plans, Cesar Vasquez drives through coastal California farm towns scanning for unmarked SUVs before dawn. He flips down his driver’s seat visor to look at a taped list of license plates he has already identified as Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) vehicles, and jots down a few new ones he suspects could be. His phone buzzes constantly – tips from neighbors, text chains from volunteers alerting to ICE activity – all in an attempt to keep his community safe from being swept up in federal agents’ widening dragnet.

This is what organizing looks like for this son of undocumented immigrants. In his home town of Santa Mariaa small farming town on California’s central coast where over 80% of farm workers are undocumented, Vasquez has become both a crucial community lifeline and a known target of federal immigration enforcement.

Vasquez began volunteering with the 805 Immigrant Rapid Response Network as a high school senior. Last August, he was hired full-time as a rapid response organizer, covering North Santa Barbara and San Luis Obispo counties, overseeing volunteers, supporting families and tracking ICE activity.

Routinely, he visits the families of detained immigrants. “There have been so many occasions where I walked through the door, and a kid was expecting their father or mother,” Vasquez said wistfully. “And it was just me, and I had to explain what happened to their parents.”

Other times, for Vasquez, the reality is personal. He recalled in December, speaking with families waiting for news about their detained relatives outside the immigration enforcement office in Santa Maria, when an ICE vehicle slowed down in front of them. The agent’s voice crackled from the car’s speaker, loud enough to carry through the open window: “How’s your mother, Cesar? We’ll go visit her soon.”

Vasquez drove straight home and found his mother washing clothes.

“I took her car keys and told her to stop everything she’s doing. My hands were shaking,” Vasquez said. “I then moved her to a secret location that I have precisely for this moment.”

Growing up as a birthright citizen of undocumented parents

Vasquez’s mother is one of the thousands of undocumented farm workers in Santa Maria whom he is trying to protect. She left her home in a tiny town in Mexico to cross the US-Mexico border at age 13 in search of a better life. Vasquez’s biological father was one of the first people she encountered – a Guatemalan American whose family was settled in California and who held US citizenship. He was also abusive and never legally married her, keeping her from accessing US citizenship, Vasquez said. When Vasquez was an infant, his mother ran away with her three children to Santa Maria, a town about 150 miles (240km) north of Los Angeles, where she found work in the strawberry fields. She has been trying to secure documentation for more than a dozen years now.

Strawberry picking is physically demanding work, and the pay is minimal. Pickers spend hours bent over in the fields under the California sun, with no benefits, no sick days and no guaranteed work once the season slows between October and March. Climate change has made the labor even more precarious, disrupting growing cycles and shrinking paychecks. Rising costs of living – rent, food, transportation – have squeezed families further. In Santa Maria, where a two-bedroom apartment can cost $3,000 a month, many families crowd into single rooms or garages.

Built on an economy of strawberries, lettuce and wine grapes, Santa Maria has long depended on undocumented labor while rendering those workers largely invisible. Many arrived during waves of Mexican migration in the 1980s and 90s, settling into a community where immigration enforcement and workplace exploitation became routine. Before Donald Trump’s recent immigration priorities, ICE enforcement in the region tended to be more targeted – focusing on people with criminal convictions or referrals from local jails, rather than broad community sweeps. ICE didn’t even have a holding facility in Santa Maria until 2015.

But since 2025, enforcement has intensified dramatically with rapid‑response trackers documenting more than 620 immigration arrests across Santa Barbara, Ventura and San Luis Obispo counties, with Santa Maria often at the center of daily apprehensions. These high‑profile raids – often carried out with unmarked vehicles and tactical gear, drawing protests and criticism from community leaders – reflect a broader national surge in immigration enforcement under Trump.

When Trump was first elected, Vasquez was only nine years old. He was already well-acquainted with the repercussions of growing up in a mixed-status household.

“I mean, it’s common for most children of immigrants to be doing things for their parents like filling out their legal forms, right?” Vasquez said. “But in fourth grade, I had to learn what a warrant looked like and what rights I had.”

He was in a Halloween costume shop, age 14, when it clicked that his fears and concerns weren’t just his own. He overheard a woman at the register, saying she had saved all year to buy her son a costume, but it didn’t fit. The store wouldn’t take it back. Her shirt was stained with strawberries, her exhaustion visible. He’d seen his own mother do the same thing countless times, so he offered to buy the woman’s son the costume.

Building a network at 14

At age 14, Vasquez founded La Cultura Del Mundo, an entirely youth-led organization that eliminates what he calls the “red tape” associated with traditional aid. They prioritize direct, unrestricted support to families in need, asking, “How much do you need?” rather than requiring forms. The group then rapidly mobilizes whatever the family requests, whether that’s cash assistance, groceries, rent help or other essential support.

In August, La Cultura Del Mundo drew national attention when Vasquez organized The March of La Pueblaa national protest against ICE raids that involved nearly 30 cities across 17 states, drawing about 10,000 participants.

Seventeen-year-old Claudia Santos is one of the many young people Vasquez has inspired. “My sister and I heard about a school walkout and just decided to go. After that, Cesar told us about a meeting at city hall, and that’s how I got involved,” Santos said. “I did it because I feel like the kids coming here from Mexico deserve a good future too.”

While Vasquez was organizing in high school, he was simultaneously struggling with his own mental health. He commuted by bus an hour each way to a school in a predominantly white neighborhood with good academic prospects.

When he told his counselor that he had anxiety, “she couldn’t understand that I was uncomfortable because I was brown in a white school, where the principal was racist and the students were racist. It led me to become really suicidal.”

Being misunderstood drove him closer to his community. He transferred to his local school and graduated early. Despite being accepted into San Diego State University, he deferred enrollment.

Most kids who grow up in Santa Maria look forward to leaving. One of Vasquez’s older sisters became a teacher in Los Angeles, the other a graduate student in the UK. But Vasquez likes that the impact of his work is immediate.

Tina van den Heever, one of his teachers from Santa Maria high school, said it was clear Vasquez was a leader with great potential: “To be honest, I worry about his safety, because as we’re seeing, the United States tends to silence people who stand up in the way that he does.”

‘I think about the kids being left behind’

During a four-day raid in late December, Vasquez’s uncle was among the 118 people detained.

“I think about the kids being left behind,” Vasquez said. “The children home for winter break whose parents never returned because of the December raids. And there was no way to know what happened to them because school didn’t reopen until days later.”

During the raids, flower vendors disappeared from the streets. When Vasquez later visited the area, the children of a family he had gotten close to told him they had gone inside after hearing his warning. They were safe.

The work – the constant alertness, the phone calls at all hours, the weight of knowing families depend on his network – has taken a toll. But he sees no alternative.

“I’m continuously preparing for the worst,” Vasquez said. He keeps a “to-go bag”, extra clothes and cash in his car.

Every time ICE picks up someone in the Central Coast valley, Vasquez plays the same song in his car: Hasta La Piel (Down to My Skin) by the Mexican American artist Carla Morrison. The lyrics speak to having and losing, wanting and not being able to say, intense love and desperate fear of loss – an homage to those who have been detained.

“They want us to be afraid,” he said. “But fear is what keeps people isolated.”

Jennifer Chowdhury reported this story while participating in the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s Kristy Hammam Fund for Health Journalism