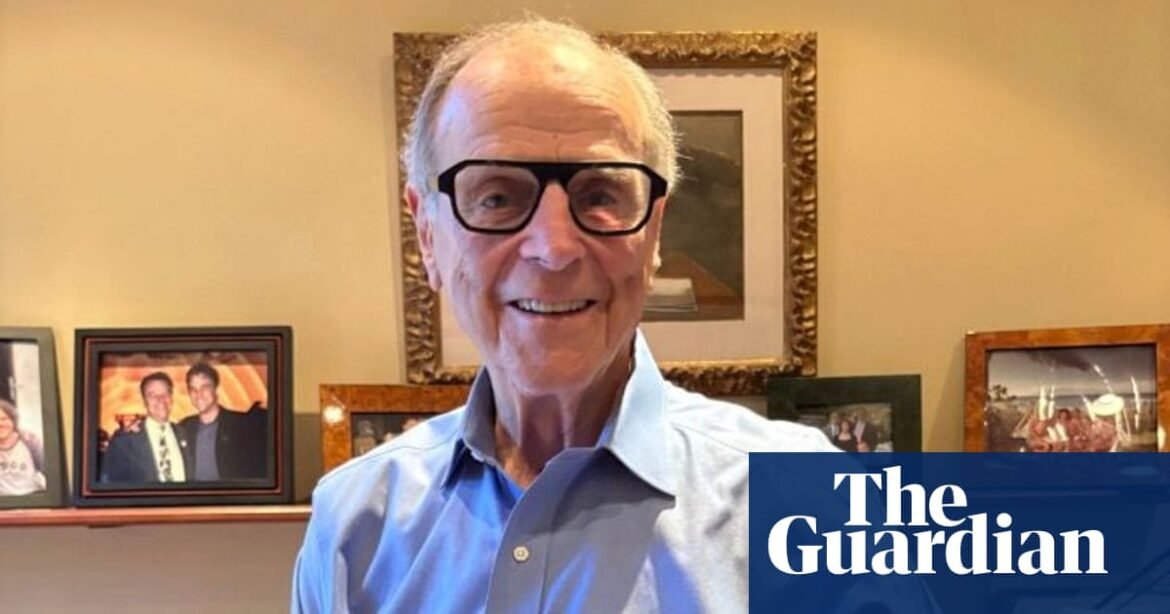

Whenever the modern era of American soccer began (the 1994 World Cup? Or the 1990 appearance by the US men? Or the 1991 World Cup win by the US women?), Alan Rothenberg was a key player.

Rothenberg came up as a lawyer under Jack Kent Cooke, owner of Washington’s NFL team, the Los Angeles Lakers of the NBA, the LA Kings of the NHL, and – crucially, the Los Angeles Wolves of the North American Soccer League (NASL), a team that started life fielding mostly players from Wolverhampton Wanderers.

From there, Rothenberg was named commissioner of soccer at the 1984 LA Olympics, then headed up the US committee that ran the 1994 World Cup, while also serving as US Soccer president from 1990 through 1998. His work with Fifa to host the World Cup in 1994 is directly responsible for the creation of Major League Soccer (MLS), whose championship trophy bore his name from the league’s founding in 1996 until 2007.

Next year, Rothenberg will release a new book. The Big Bounce: The Surge That Shaped the Future of US Soccer is a chronicle of his time in positions of power as soccer grew in popularity in the United States. He spoke with the Guardian about his history in the game, the influence of big business on sports, why Americans have gravitated to soccer, and how Fifa’s efforts at political influence have changed over time.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

––

What are you anticipating for this World Cup draw?

It’s gonna be interesting. Let me put it that way. I take credit for a lot of things that we did in ‘94 that had never been done before, and one of those was turning the draw into a big event that wasn’t just deciding which groups would exist. We had a lot going on, we were in Las Vegas. DC is different. And I think we all know why it ended up in DC. And I also think it means there’ll be a teeny bit of a political overload on it. [In 1994] we we had a video message from President Clinton, but it was just a small portion of the event. Obviously both President Trump and Gianni Infantino made this a very personal project of theirs, and so they’re going to be probably more prominent than what we’re accustomed to seeing. But it’s going to be great at the end of the day.

I noted this passage from your book: “I was a sports lawyer before there were sports lawyers. In those days … the business side of sports was run by ex-jocks. They played, they coached, and then they became general managers. They knew the sport. But as the dollar signs started to pick up and contracts grew more complicated, it changed dramatically.” Is there any part of you that wonders if it’s swung too far the other way? Do you wonder if business interests have an outsized influence on the way sports are run these days?

[The business of sports] is where it is because of a free market economy, and a free market for the fanbases. If fans were really upset and stopped going to games, stopped watching it on television, it would change. But it’s going the other way.

It’s the case for some teams, though. I was just looking at crowd shots at a New Orleans Pelicans game where it looks like there’s like 400 people. How do you square the national interest in sports that you point out with images like that in local markets where teams are clearly not connecting with their fans, for one reason or another?

I think local [interest] still dominates. As things get toward final competition, playoffs, championships, it becomes more national. We just had a great World Series. But on a day-to-day basis, the local Dodgers TV package is way more fruitful to them than their participation in the national package. They have 162 games, so it’s a lot of product, a lot of inventory, but that’s true in most [leagues]. You mentioned the Pelicans – their fans can’t stand the fact that the team is really pathetic, so they’re not going [to the games]. On the other hand, I will bet you anything when it gets to the NBA Finals, and it’s Oklahoma City, who people wouldn’t even know about otherwise, those people in New Orleans who are basketball fans will be watching it.

Do you think that soccer is different from that sort of dynamic you’re describing? I think a lot of people are attracted to global club soccer because very often those teams were community assets first, and then they became businesses later. And that creates this dynamic among the fans where they’re dedicated no matter what. What do you think that says about what fans want out of soccer in the United States?

I think there’s probably more of an emotional connection between soccer fans and their team than in most other sports. I mean, I don’t know how any other sport, and frankly, in any other country, would have had the experience that went on with the Premier League when the Super League was proposed. It was basically a fan revolt that got everybody to, at least temporarily, back off.

Lamar Hunt said that you have to build up local teams and have local fans, and that’s going to be the backbone of the growth of the sport. I think that’s true. I mean, I look at the phenomenon LAFC have created out of nothing. They set that group out in the south end of the stadium, it’s as if they transported them from Brazil or from England. You don’t really see that in other sports.

How would you describe the American soccer audience to someone from another country, where soccer is the No 1 sport and always has been?

I think that there’s a huge appreciation for the sport and a huge knowledge base for the sport, and that’s good news, and it’s also challenging news. The good news is there’s a really huge number of true soccer fans in this country, and that’s the core, the fanbase for MLS, for NWSL and all the USL teams. The challenging part is the fans are so sophisticated that they follow teams in Europe. I mean, it’s great for the sport, but the challenge is that we’re trying to grow the support for the American teams, and I think that’s where 2026 is going to help a lot. I just think that there’s going to be an exponential growth of soccer fans, which is going to mean more television, more revenue, which means MLS can be more competitive in the international market. That plus their change to the international calendar, I think you’re going to see more top players still in their prime coming into MLS, which in turn, I think will again create greater audiences.

after newsletter promotion

There are a lot of logistical questions surrounding the 2026 World Cup, particularly around transportation – getting people into and out of the cities but also to and from the stadiums, often in places without robust public transit. These were issues in 1994. How did you get over them?

Soccer fans, I think, are really unique. They find their way. People have talked about some of the immigration issues making people reluctant to come. I think those soccer fans will find their way over here no matter what. And similarly, frankly, to the extent there isn’t or wasn’t public transportation, it was readily available. I think each city is going to do a good job of putting out pamphlets and brochures and things so that visitors know their way. These cities really rely on the fact that people are going to go to restaurants, bars and museums, and so it’s going to be a big economic boost to the cities, and they’re going to do everything they can to inform fans what the options are. We really did not experience any kind of significant issue.

Do you feel that dynamic also applies to ticket prices? People are spending thousands on tickets to these games, and others can’t go because of how dynamic pricing has impacted the cost. Fifa has a responsibility to create revenue for their member associations, but do they also have a responsibility to allow fans to affordably access this tournament that’s meant to be so transformative?

I equate it to a Taylor Swift tour. Somehow people are able to pay the price and find their way, in some cases, to remote venues. So where there’s a will, there’s a way, and especially in soccer fans, there’s a will.

[Dynamic pricing] is the reality of today. With Taylor Swift, you’ve got young people somehow coming up with several thousand to go to a concert. And if they didn’t have dynamic pricing, it would still be the same, because everybody would go to the after-market, and they’re going to end up paying what the market price is. It’s today’s world. And yes, it does mean that a lot of middle-class, working people and their families are priced out. I don’t mean to sound unsympathetic, but it’s the free market at work.

The good news, at least, is Fifa has been insistent on making sure that every host city has a major fan festival. In some ways, that’s as good or a better experience. It’s a festival, and you’re there with thousands of people, jam packed. So you don’t see the game live, but you got it on a massive screen, so you probably actually see the game better than if you were at the stadium.

You mentioned before that the 1994 opening ceremony was not overly political, but Fifa has clearly been way more willing to engage politically around World Cups than they have been in the past. Do you agree with that approach?

I don’t think it’s necessary. Infantino, for each of the World Cups since he’s been president, has sort of made himself a part of the government in power. It doesn’t hurt, because you want good cooperation, but I don’t think it’s necessary. I mean, we had first George HW Bush and then Bill Clinton in 1994 and they were fine. They were supportive. They were, you know, we went to them when we needed something, and it was, frankly, pretty infrequent, and they gave moral support. We didn’t try to get them to be engaged in the operation, and they didn’t try to insert themselves. I think you just have a different dynamic, both in Infantino and in President Trump. It’s unusual. It’s good and it’s bad. It’s good in the sense that it’s often great to have your head of state taking a personal interest in the event. He’s going to be darn sure that it works. Does it put a political overhang on the tournament, which probably upsets a lot of fans? Yeah.

But again, as a practical matter, you’ve got to do things locally. Here we got the LA Olympics coming, and the head of that is Casey Wasserman, part of a longstanding, influential Democratic family. He went back to meet with Trump to get government support for the Olympics. A lot of people here were saying “Well, what a hypocrite.” Come on. He’s got a job to do. His job is to have a successful Olympics, and it’d be awfully nice to make sure you got a great relationship with your government. I love your media, but the media likes good stories, and so they’ll grab anything they can.