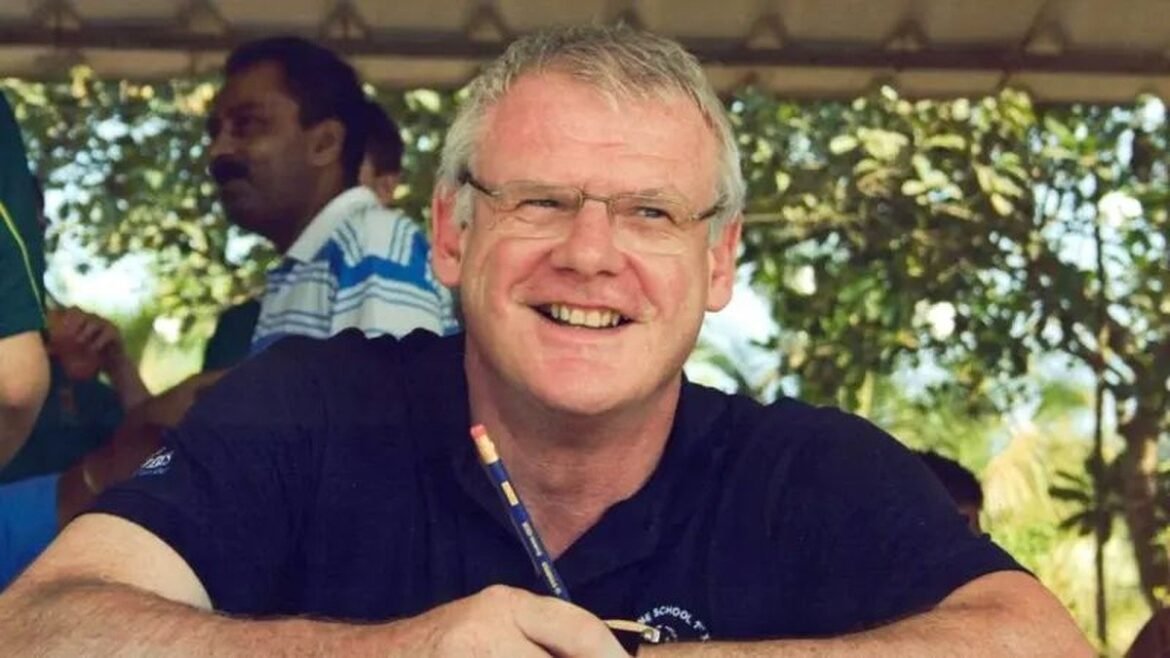

Lawyer Andrew embezzled hundreds of thousands of pounds from his clients Personal archive via BBC Frances had just arrived at work when she received a phone call that turned her life upside down. Police officers had arrested her husband, Andrew, a lawyer, on charges of fraud against clients, and were searching the family home, where the couple lived with two children. Andrew’s office, in a leafy village south of Manchester, England, also looked like a scene from television: cordoned off with yellow police tape, staff in shock and documents being boxed up. His office held powers of attorney for many elderly people with dementia. But police discovered that hundreds of thousands of pounds worth of customers’ money had gone missing. Agents later discovered that Andrew had spent this money on live sex, prostitution and antiques websites. This happened 12 years ago. A court case revealed that Andrew’s impulsive behavior was caused by medication he was taking to treat Parkinson’s disease. He robbed 13 of his clients. Eleven were over 80 years old, and some were sick. They had a total of £600,000 withdrawn from their accounts. An 87-year-old woman who lived in a nursing home died shortly after the robbery, and her heirs did not have enough money to pay for the funeral. “People didn’t want anything to do with us, and I completely understand,” says Frances, remembering what Andrew had done. Meanwhile, his daughter, Alice, says her father “never forgave himself.” Andrew’s behavior would have tragic consequences later. His case is extreme, but far from isolated. Over the past year, we’ve spoken to dozens of families whose lives have been destroyed by impulsive behaviors caused by a class of medications known as dopamine agonists. This includes the development of new sexual desires – such as addictions to pornography and sex workers – but also compulsive shopping and gambling that has cost people tens or hundreds of thousands of pounds. Silent danger Medications are an established treatment for Parkinson’s. It was prescribed 1.5 million times by general practitioners in England alone last year. The recommendation from the NHS, the United Kingdom’s National Health Service, is clear: if you are taking these medications and have any concerns, you should speak to your doctor. One in six Parkinson’s patients taking these medications has impulse control disorders — the clinical term for this behavior — according to a 2010 study of just over 3,000 people. Many of the people interviewed by the reports said that they had no history of impulsive behavior before taking the medications and had no relationship with the medication when they started taking them. They claim that doctors did not warn them adequately or monitor the effects of the medications. In the summer of 2013, the weekend after his arrest, Andrew tried to put on a brave face for his family. But that Sunday he passed out at home and was taken to the emergency room. Andrew with his son Harry, when he was little Personal archive via BBC He had been diagnosed with Parkinson’s a few years earlier, and when he started having tremors, doctors prescribed a medicine called Pramipexole, which is also sold in Brazil. The effects were “miraculous”, according to Frances. Pramipexole and similar medications work by increasing the activity of dopamine, a chemical that helps regulate our movements but also drives feelings of reward and pleasure. Andrew’s tremor, caused by Parkinson’s, eased dramatically, his family says, and he soon returned to playing tennis. But in the emergency room, after she fainted, a doctor asked Frances if she knew that Pramipexole could cause a series of impulsive behaviors in people who take it. Frances says it was a “terrible shock”. She couldn’t understand why she had never been notified, despite accompanying Andrew to every appointment. The medication’s potential side effects, she says, finally explained Andrew’s compulsive shopping, although at that time she had no idea the true extent of his spending. See videos that are trending on g1 Before his diagnosis, Andrew used webcams and sex chat sites approximately once a week. But in the year after he started using the pills, he made almost 500 payments to these sites. He even spent more than £100,000 on a single website, using his clients’ money. He also spent almost £80,000 on sex workers in just four months and when he was arrested his mobile phone contained the numbers of 90 different escorts. Andrew, who had always been a big history buff, also began compulsively buying antique pens, pottery and cricket memorabilia. He spent £85,000 on eBay in the six months before the raid. “My father has been so embarrassed since he was arrested that he basically hasn’t left the house,” says Alice. For more than a year, the family waited for news from the prosecutor’s office. In the end, Andrew was accused of fraud. Frances says the couple’s son Harry “loved his father very much” but the boy, who had mental health problems, found it “very difficult to deal with what happened after the arrest”. Andrew served two years of his four-year sentence in a prison in Manchester, England Getty Images via BBC Harry’s mental health deteriorated so much that he was compulsorily hospitalized. He returned home and then disappeared. Weeks later, his body was found. He had committed suicide. In 2015, in court, Andrew pleaded guilty. During sentencing, the judge said he had wasted his clients’ money on various “sexual excesses” and “absurd extravagances”. The judge said he believed Andrew’s behavior was caused by the drugs he was taking, but argued that he was a lawyer and was still able to conduct his business competently in other ways. As a man with family, friends and counselors, the judge said, Andrew should have sought their help and identified the effect the medication was having on him. Andrew was sentenced to four years in Manchester prison, known as Strangeways. During the investigation, all of Andrew’s assets were frozen to recover some of the money stolen from his clients. The family was also unable to pursue a medical malpractice lawsuit against Andrew’s doctors because legal standards may prevent recovery of damages linked to a serious criminal act. Frances and Andrew divorced while he was in prison. After his release two years later, he moved into assisted living. Prison had a devastating impact on Andrew, according to his family, and the Covid-19 pandemic lockdowns were particularly difficult for him, who stopped taking the medication immediately after discovering its effect. Parkinson’s symptoms, however, worsened. “I think his whole life was completely destroyed,” says Alice. “Yes, because of the Parkinson’s, but mainly because of the medication.” In October 2020, Andrew committed suicide. Political discussion Andrew’s death does not appear on the UK’s public Yellow Card register, the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency’s system that collects reports of adverse drug effects. Nor will it include the case of his son, Harry. The harm caused by dopamine agonist medications to other families has also not been recorded. Some told us they lost their life savings or even their homes due to gambling addiction or compulsive shopping. Many also said they were left without a means of seeking justice for their losses due to the challenges of growing class actions in the UK and the difficulties in meeting the requirements of a medical negligence case, where they would have to prove they were not warned. It has been more than 20 years since these were discovered to cause impulsive behavior. Last year, the BBC revealed how GSK — the British pharmaceutical company that first licensed this type of Parkinson’s medication in the UK — discovered, as early as 2003, a link between the medication and what it called “deviant” sexual behavior. Three years later, warnings appeared, but they only listed the potential for “increased libido,” “harmful behavior” and “altered sexual interest.” These leaflets still do not inform the frequency with which the disorders may occur. Now, Layla Moran, chair of the British Parliament’s Health Committee, is calling for warnings to list how frequently the disorders occur and specify the types of behaviors, such as pornography addiction, that may arise. Liberal Democrat MP Layla Moran has written to the UK’s medicines regulatory agency asking it to strengthen warnings BBC “It’s not just a side effect affecting the individual. It’s affecting families and communities and creating new victims,” she said. “What does ‘impulsive behavior’ mean and how likely are patients to develop it? Currently, patients don’t have this information, and without it, how can they be expected to mitigate this behavior?” he asks. Moran says the Yellow Card program is “not suitable” for reporting side effects that people consider shameful. The government described the findings of the BBC investigation as “extremely worrying”. However, the regulatory agency said there are no plans to change the alerts. These sexual behaviors are “individualized”, says the agency, and therefore it is not possible to include an “exhaustive list” in the information leaflets. The agency previously told the BBC that it does not list the frequency of impulse control disorders because many people do not report them. What drugmakers say GSK said its drug has been extensively tested, approved by regulatory bodies around the world and prescribed for more than 17 million treatments. The company said it shared its report on safety concerns with regulators. The medication prescribed to lawyer Andrew, pramipexole, is manufactured by Boehringer Ingelheim. The company did not comment. In 2017, doctors were required to provide Parkinson’s patients and their families with verbal and written information about the risk of impulsive behaviors and to regularly monitor their development, in line with guidelines from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. But the report has heard from many Parkinson’s patients who have been prescribed the drugs since the introduction of these guidelines that they have not been properly warned about the risks. Some say they currently suffer from impulsive behaviors. Alice and Frances have moved hundreds of miles away from the village where they lived, but the pain remains with them. “My life was taken from me: my home, the community I lived in, but most of all, my son,” says Frances. “I just don’t have the words to describe how devastating this is.”

Source link

‘My husband embezzled more than R$4 million to spend on sex and antiques because of medication side effects’

19