When 13-year-old music prodigy Itzhak Perlman performed on “The Ed Sullivan Show” in 1958, viewers could see his extraordinary talent. What they couldn’t see were the braces and crutches he needed to walk.

Perlman was four when he contracted polio. “I was already running and walking, and I remember one morning when I got up and I couldn’t stand,” he said. “I usually would stand up in the bed. And then I would go out and get dressed and so on. All of a sudden it was like, Stop. Can’t do that anymore.“

Perlman, like hundreds of thousands of other children around the world, was infected by the polio virus before the first vaccine against the disease became available in 1955. He missed the vaccine by about six years. “Yeah, I’m here to tell you that’s what happens when you’re not vaccinated,” Perlman said. “My life was changed forever. My parents were upset. Ugh, they were so upset.”

Steve Oroz/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

The polio virus could cause paralysis so severe, some children needed machines to breathe. At the height of the pandemic, in the late 1940s and early ’50s, thousands of children were kept alive by iron lungs.

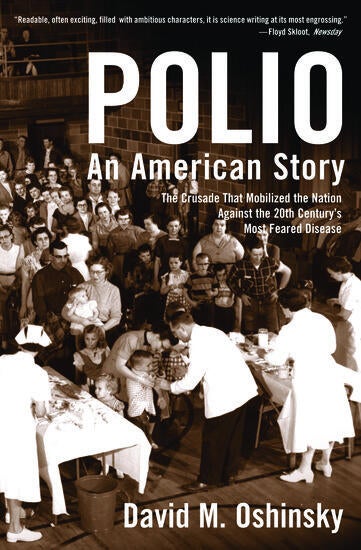

“There was no protection, and there was no cure,” said historian David Oshinsky, a professor at NYU Grossman School of Medicine, and author of the Pulitzer Prize-winner “Polio: An American Story.” “You could be a hands-on parent, a hands-off parent. It didn’t matter. You could not protect your child from polio.”

Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

Polio virus is spread through water, food, and close contact with an infected person. There’s no cure or FDA-approved antiviral treatment.

Oshinsky remembers the toll it took on his childhood in the 1950s: “You had to stay out of crowds. You couldn’t go bowling. You couldn’t go to the movies. You couldn’t go swimming. Beaches would close. Swimming pools were closed. I remember my parents every week giving me a polio test: Could I touch my chin to my chest? Could I touch my toes? And the slightest stiffness would bring a panic.”

But what happened to that fear? “What happened to that fear was vaccines,” Oshinsky said.

The first polio vaccine was developed by Dr. Jonas Salk in 1954. Before it was released, it was tested on nearly two million children, with some getting the vaccine, and some getting a placebo. “Try to think of an instance today where they would have an experimental vaccine, and you’d have parents rush two million kids into line,” Oshinsky said. “It’s unheard of today.”

The vaccine was found to be safe and effective, and cases of paralytic polio plummeted. Parents rushed to get their kids vaccinated.

And what did Oshinsky’s mother do? “Push me into line!” he laughed.

Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

In 1961, an oral polio vaccine developed by Dr. Albert Sabin, essentially vaccine drops given with a cube of sugar, was widely adopted in the United States and abroad.

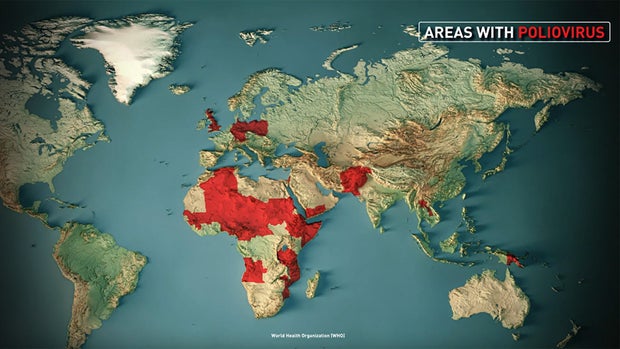

However, today the virus still circulates in certain parts of the world.

CBS News/WHO

Oshinsky said, “If that virus comes to the United States and we have a significant percentage of the population unvaccinated, polio is going to come back. It is only a plane ride away.”

If a person with polio comes in contact with enough people who are immune to it, the virus hits a dead end. That so-called “herd immunity” helps protect the unvaccinated, and the estimated 20 million or more Americans with weakened immune systems.

All 50 states require polio vaccination for school attendance. But in recent years, more and more parents have used exemptions to avoid vaccinating their children, raising concerns polio could return.

During a recent podcast interview, Dr. Kirk Milhoan, head of the CDC’s advisory committee for immunization practices, implied it might be time for the polio vaccine to become optional:

“If you look at polio,” Milhoan said, “we need to not be afraid to consider that we are in a different time now than we were then. Our sanitation is different. Our risk of disease is different. And so those all play into the evaluation of whether this is worthwhile of taking a risk for a vaccine or not.”

Milhoan declined a request by “Sunday Morning” to be interviewed for this story.

Oshinsky said, “This seems to me to be a situation where children’s lives are at risk, and that changes the dynamic.”

Asked why some parents are under the belief the polio vaccine is not necessary, Oshinsky replied, “Most people think polio is gone. They really don’t have a sense that it’s still percolating in parts of the world.”

Just four years ago, an international traveler brought the polio virus to an under-vaccinated community in New York State. Without herd immunity to protect him, a 20-year-old unvaccinated man became paralyzed.

For Itzhak Perlman, the choice to vaccinate against the disease that left him paralyzed is clear: “For 70 years, we have been doing very, very well and almost eradicating polio. Why take a chance? Don’t take a chance. Believe me, it’s not worth it. It’s really not worth it.”

Jon Naso/N.Y. Daily News Archive via Getty Images

WEB EXCLUSIVE: Extended interview with Itzhak Perlman (Video)

The famed violinist talks with Dr. Jonathan LaPook about his experience after contracting polio as a child, several years before the development of a polio vaccine, and the obstacles in life to which he has had to adjust because of his disability. He has advice for those who question taking the vaccine. He also talks about the effect of music on the brain, and how he wishes to be remembered.

For more info:

Story produced by Mary Raffalli. Editor: Carol Ross.

See also: