The Dutch Grand Prix was never a happy hunting ground for Bruce McLaren, who registered seven DNFs at Zandvoort and two non-points finishes in the nine championship races he started there. But on the 88th anniversary of McLaren’s birth, cars carrying his name enjoyed a formidable margin of superiority to their Formula 1 rivals: more than two tenths of a second in hand over third-placed Max Verstappen, and half a second from fourth-placed Isack Hadjar.

Maybe not the kind of dominance Jim Clark enjoyed in the 1964 event, when Bruce finished a distant seventh, two laps down, while the victorious Clark crossed the line nearly a minute ahead of second-placed John Surtees. The margins are different in contemporary F1, especially when it comes to the McLaren team-mates. Just 0.012s separated Oscar Piastri and Lando Norris in Q3, only the second timed session in which Piastri was quicker than his stablemate.

During the Hungarian grand prix weekend, Charles Leclerc had been as surprised as anyone else to snatch pole position off the table at the final time of asking. In Zandvoort nobody was holding out much hope of a repeat; McLaren’s advantage was such that a Piastri or Norris pole seemed preordained.

But all the signs were pointing towards Norris being the one who emerged on top. How Piastri reversed the trend was a testament to the way the poker-faced Australian unobtrusively builds during a grand prix weekend.

The final margin was so fine Norris struggled to explain it.

“Both my [Q3] laps were good,” he said. “I don’t think many people improved on their second runs, so I don’t know if the track got a little bit trickier or slower in the second run, but both were pretty close, I think.

“Again, within half a tenth or a tenth of pole position. Tricky also with the wind. It can easily just favour you or not favour you. And, yeah, one hundredth is pretty minimal.

Lando Norris, McLaren, Oscar Piastri, McLaren

Photo by: Sam Bloxham / LAT Images via Getty Images

“Even coming out of the last corner, I’m a little bit up and I lose like two hundredths by the time I get to the start-finish line and that’s pole position gone for me.”

In the immediate aftermath of the session, quizzed in parc ferme by Jolyon Palmer, Norris had suggested the weather was a factor: “With the wind like this, a lot of it’s down to luck as well.”

But does this suggestion stack up?

It’s true that both McLaren drivers set their fastest laps of Q3 on their first runs. Their second runs, on fresh tyres, were still quicker than Verstappen’s best effort, though this time Norris’s run was 0.004s faster than Piastri’s.

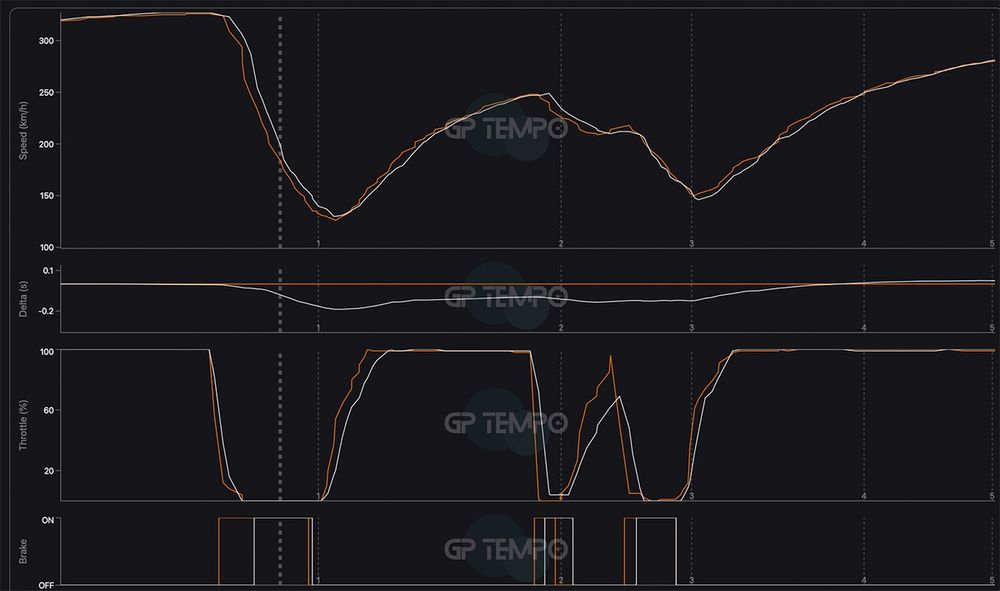

Scrutiny of the GPS data reveals how the balance swung between the two McLaren drivers on that ultimately decisive first Q3 run. Norris (illustrated by the white trace) carries more speed into Turn 1 by dint of lifting off the throttle slightly less steeply than Piastri (orange trace), then getting onto the brake later. His advantage peaks at 0.188s as the track opens up at the exit.

But by this point Piastri is at 54% throttle and Norris is feeding it in at 20%. The gap narrows slightly to below a tenth of a second, then begins to open again at Turn 2 as again Norris is later on the brakes and doesn’t quite clear the throttle, running at 235km/h to Piastri’s 226km/h mid-corner.

In the short run between Turns 2 and 3, Piastri is able to pick up the throttle more and chip away at his team-mate’s advantage. From mid-way through the banked Turn 3 Piastri applies the throttle more decisively and is at 61% to Norris’s 32% before they’ve even touched the exit kerb.

From there the gap evaporates and Norris is 0.024s down before the sweeping Turn 5-6 section. This begins to compound as Norris takes a bigger lift through Turn 7 (52% throttle rather than 72%) and, from the apex of that corner, the gap opens from 0.063s to 0.110s in Piastri’s favour on the run to Turn 8.

There, Piastri loses as little momentum as he bleeds off the throttle earlier, more sharply and fully than Norris, and requires a dab of brake which Norris doesn’t. An rpm spike here suggests some wheelspin as Piastri gets back on the throttle much more decisively at the apex as the corner opens out – and yet the gap remains relatively static, even growing to a peak of 0.135s on the short run between Turns 8 and 9.

At Turn 9 they brake at the same point, but Norris is off the throttle earlier and more gradually. Piastri gets off the brakes first but the more ragged application of throttle, and accompanying rpm spike, suggest he is managing wheelspin. The gap briefly drops to below a tenth of a second again before opening out briefly towards Turn 10.

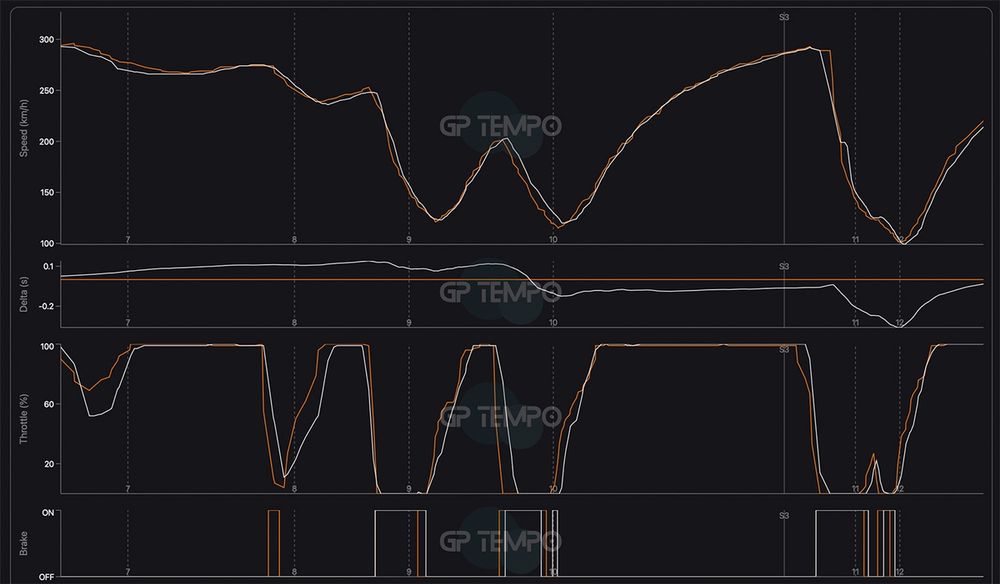

Piastri is first on the brakes at Turn 10 and much earlier off the throttle, enabling Norris to nibble away at the gap again. From braking zone to apex Norris is at least 10km/h faster; Piastri is earlier on the throttle just after the apex of Turn 10 but by this time the damage has been done and Norris is 0.121s up.

Piastri is slightly quicker down the straight towards Turn 11 and Norris has just 0.039s in hand as they get on the brakes. Norris is later and more sharply off the throttle, both have slight ‘blip’ just before Turn 12.

In that short section as they round Turn 12, Norris is again able to carry slightly more speed through, opening the gap to 0.359s at the apex. But Norris is on the brakes for longer, Piastri on the throttle earlier, and the gap immediately starts to close on the straight between Turns 12 and 13.

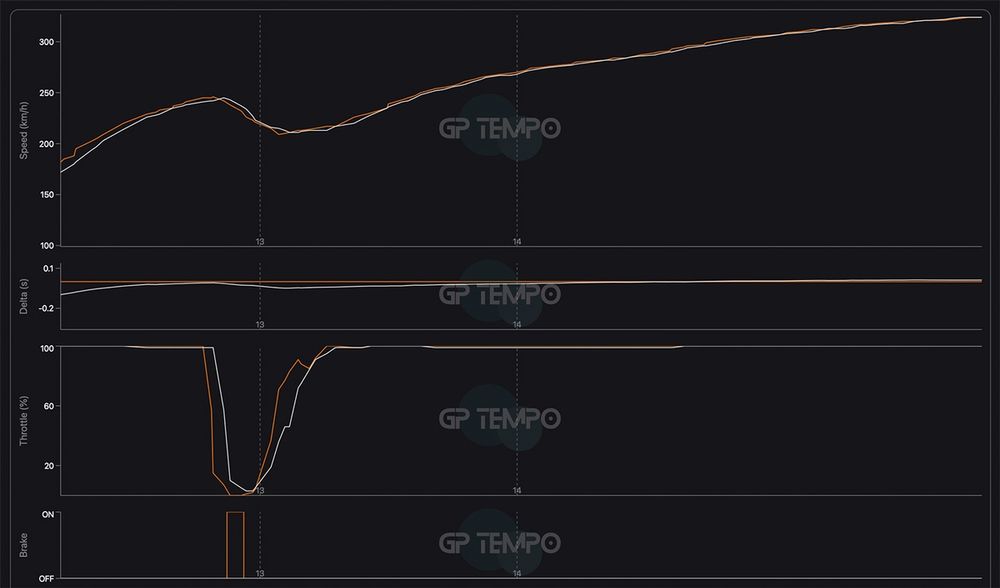

That loss of momentum proves costly for Norris as he is on the back foot from there. His advantage is down to 0.009s as they lift for Turn 13 and he gets a brief respite as Piastri backs out of the throttle earlier and needs a brief dab of brake.

Piastri gets on the gas earlier, but has to feather it and the gap opens out again to 0.047s. But this shrinks to 0.014s through Turn 14 and, by the time the cars reach the timing line, Piastri has turned the tables and is 0.012s up.

Scrutiny of the data only shows us so much, though. Piastri came up behind Hadjar towards the end of the lap and enjoyed a slight tow at the crucial moment, giving him a 2-3km/h advantage over Norris as the track opened out.

So while the gusting wind was certainly ever-present, it was a different type of air movement which proved decisive.

In this article

Be the first to know and subscribe for real-time news email updates on these topics