Logan Coleridge was used to taking hits in football. He’d been playing since he was 6 years old and had sustained several concussions. But after a helmet-to-helmet impact during his freshman year of high school in August 2023, he started having debilitating symptoms.

The New Jersey teen said he was very dizzy and had trouble balancing. His memory was “terrible,” and he had a “severe” light sensitivity, he said, along with “terrible headaches.” Previously a strong student, he now struggled to focus in the classroom and couldn’t remember school assignments or what he read in class.

“I’ve got concussions in my past, and it wasn’t like a normal one,” Logan said. “I knew it was something else.”

Becky and Barry Coleridge

More alarmingly, Logan wasn’t getting better. Several months of physical therapy had no effect, said Becky Coleridge, Logan’s mom. A neurologist who had been treating Logan since his diagnosis with abdominal migraines the year before prescribed two medications, both of which had negative side effects. An orthopedic doctor suggested looking at his neck. Other practitioners had no answers. Coleridge wanted doctors to prescribe an MRI, but wasn’t able to get one. Meanwhile, Logan was missing school almost every week. Over-the-counter medications couldn’t dull the headaches, and they were becoming more frequent.

In early spring 2024, Logan was able to see a concussion specialist after a particularly bad headache kept him from going to school.

“The first thing he said was ‘Nobody’s given this kid an MRI?'” Becky Coleridge remembered. The specialist prescribed the scan, as well as an X-ray of Logan’s neck. The Coleridges thought the scans might show Logan had an issue with his occipital nerve, which runs from the neck to the scalp.

The results were much harder to hear: Logan was diagnosed with an arteriovenous malformation, or AVM. It was a condition that he and his parents had never heard of before.

“Everything we read was very scary,” Becky Coleridge said. “At that moment, we realized the danger he had been in.”

Becky and Barry Coleridge

What is an arteriovenous malformation?

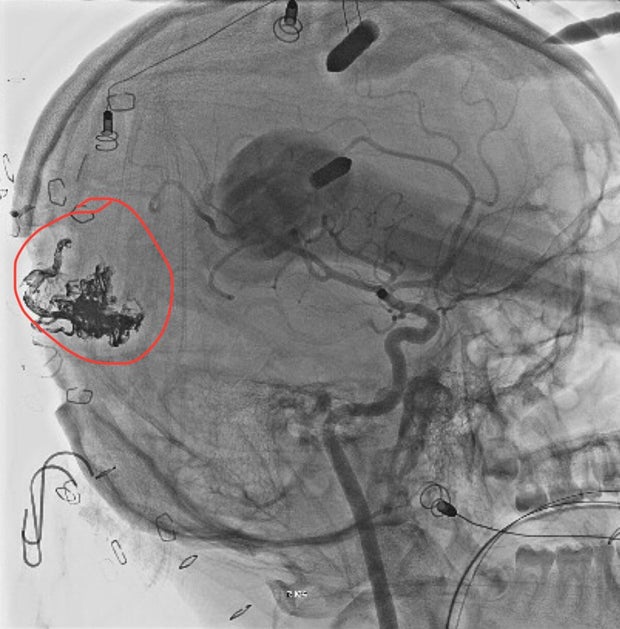

An AVM is an abnormal tangle of blood vessels in the brain, said Dr. Andrew Russman, head of the Cleveland Clinic’s stroke program, who was not involved in Logan’s care. AVMs put “a lot of pressure on the vein side” and can produce a variety of symptoms, he said. The biggest risk with an AVM is rupture, where the vessels burst and cause bleeding in the brain.

In a case like Logan’s, where the AVM hasn’t ruptured, there can still be symptoms. Those symptoms can affect a person’s motor skills, sensory and visual perception, language abilities and the way they walk, Russman said. The effects can vary depending on where in the brain the AVM has formed, Russman said.

The Coleridges had two options to treat Logan: Radiation therapy, a non-invasive technique that uses focused radiation beams to target and slowly destroy the AVM, or surgery. Radiation therapy could take too long, the family decided, and so they decided to have Logan treated by Dr. Howard Riina, a cerebrovascular neurosurgeon at NYU Langone.

Becky and Barry Coleridge / NYU Langone

“He couldn’t go to school. His whole life was impacted by these headaches,” Riina said. “They wanted an immediate solution.”

Riina said the AVM, which was on a “headache spot” in the occipital region of the brain, was likely the root of Logan’s symptoms. People are born with AVMs, Riina said, and they grow as the body grows, which can cause increased symptoms.

“Obviously, you don’t want to have multiple things going on in your head, but the concussion is what led to the imaging, which led to the diagnosis of the AVM, which was probably what was causing the headaches all along,” he said.

Raising awareness and “focusing on a new beginning”

Logan underwent surgery on July 17, 2024, nearly a year after his symptoms began. Riina performed a craniotomy and removed the AVM. Three days later, Logan was discharged from the hospital to continue his recovery at home. Logan said it was a “lonely” way to spend his summer vacation. Even as his recovery progressed, he couldn’t participate in the sports he loved.

“I couldn’t really do the things that I love normally doing, like exercising, playing football was a big thing for me. I was just stuck in bed, pretty much having minimal activity,” Logan said.

Becky and Barry Coleridge

Now, Logan has only the occasional headache, and the pain can be treated with medication. He has follow-ups at NYU Langone, but Riina said everything has come back clear. The Coleridges are working to encourage early testing: Becky Coleridge said she wishes Logan had received an MRI earlier so that months of suffering and confusion could have been avoided.

This year has been a complete turnaround, Logan said. He no longer misses school. He celebrated his 16th birthday and took driving lessons. This summer, he spent almost every day at the beach with friends. This month, he’s gearing up for a return to the football field.

“The whole experience was a fork in the road for me that I had to get through,” Logan said. “I’m leaving that time in my life in the past and focusing on a new beginning.”